DFID Research: understanding TB and HIV related stigma in Zambia

Stigma related to TB and HIV has severe implications for treatment.

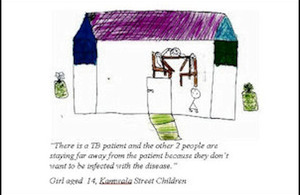

Drawing by a Zambian street child describing the stigma experienced by TB sufferers

DFID and USAID funded research has shown that Tuberculosis-HIV stigma has severe implications for the treatment of TB Patients. Researchers interviewed TB patients, people living with HIV and AIDS, children and youths, religious leaders, health professionals, caregivers, educators, farmers, employers and NGOs in urban and rural communities in Zambia, to ascertain people鈥檚 perception of those with TB.

In communities with high HIV prevalence, TB and HIV have become closely linked and a new disease stigma has unfolded - namely TB-HIV stigma. A common nickname for people assumed to have AIDS and for TB patients is 鈥渒anayaka鈥� - a local term meaning 鈥渢he light is on鈥�, referring to see-through frailty, impending death (since the light of life can go out) and the public symptoms of such diseases.

HIV has changed the social experience and understanding of TB, creating confusion about what TB is, whether it is still curable and recognition that it is more deadly than it was before HIV/AIDS. One rural interviewee said, 鈥淭he TB of today should be given another name because it can no longer be cured鈥�. TB has become seen as a sign of HIV and indeed, sometimes the distinction between TB and HIV falls away altogether.

What are the causes and effects of TB stigma?

The key causes of TB stigma are the judgment, blame and shame that accompanies a TB diagnosis (with the TB patient being held culpable for their infection), the fear of being infected with TB through close contact, and poor public health responses to controlling TB that include recommendations for social isolation of TB patients and use of designated spaces in health centers for TB patients. Similar to the case with HIV, women and children and more marginal groups in the community are more vulnerable to TB stigma - they are more susceptible to being judged and blamed and more likely to be rejected or sent away.

TB-HIV stigma contributes to delays in seeking treatment for TB and to patients denying or hiding a TB diagnosis. One business woman stated, 鈥淚t is on rare occasions that TB patients [reveal] their status because as a community, when we see that someone has TB, we say they have AIDS and so they decide to keep it to themselves for fear of being isolated鈥�. Not everybody is as well-informed as the 12-year-old orphan whose own parents had both died of TB: 鈥淭B is an airborne disease but a person cannot get infected once the patient is on treatment. Both TB and AIDS patients need proper care. They don鈥檛 have to be separated because of their status - they need encouragement鈥�.

There has been a slow response to the social consequences of the intertwining of TB and AIDS from medical experts and researchers, but a gradual shift towards a more integrated approach to TB and HIV care has been catalyzed by the roll-out of anti-retroviral treatment (ARV). TB diagnosis is an excellent entry point for HIV counseling and testing and, for those TB patients living with HIV, for ARVs and other HIV services. There is an opportunity to adapt HIV anti-stigma education approaches specifically for TB as well as integrating anti-stigma education into a wider strategy of TB patient empowerment. Decreasing TB-HIV stigma will improve patient health and make having TB and HIV less dehumanizing.

More information

See the DFID project record: